In panel conversations between musicians, researchers, journalists, organisers and promoters we found and heard about a range of approaches to trying to revitalise the (jazz) festival experience and the jazz scene during the 12 Points Festival discussion days on ‘Jazz Futures 2016’ here in San Sebastian this week. This was felt important for a number of reasons, including that in some countries the big all-star jazz festival is fading, its audience diminishing, while elsewhere, perhaps ironically, perhaps in a connected way, there is a surfeit of festivalisation of culture, in that festival in its ubiquity has become everyday, even banal, and no longer the intense, heightened and exceptional. Here are some of those diversifying approaches, familiar and perhaps not so.

-

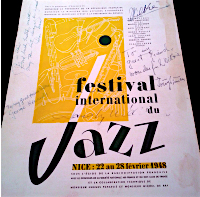

12 Point Jazz Futures discussion, San Sebastian Jazz festival or event as immersive experience—music, yes, but also costume, design, actors and dancers, food, theatre and masque, historical reconstruction of scenes from jazz past with a promenading audience

- Jazz apps, and audience interactivity via mobile digital technology

- Electronic deconstruction of the live music event in the very next concert that follows, so the audience hears fresh the new music it just heard, where sometimes the remix is better than the original (though, yes, “sometimes it’s shittier”)

- An emphasis on creative curation rather than simply programming or organisation and presentation of a series of concerts

- Cross-cultural and cross-arts dialogue. Whether improvised arts (music, dance, animation) working with each other in the moment, or a festival of improvised music that must include literature and vice versa

- A continuing struggle with the Jazz word: a European jazz festival director says I don’t want to use the term “jazz festival”, it’s off-putting for a new audience, others saying we lose something worth cherishing and celebrating if we reject it (i.e. a century of live and recorded music)

- The on-going core relevance of jazz and music education: new musicians, new networks and events, new energy, and new audiences

- The regular inclusion of academic research in the festival programme, an openness to it in the scene more generally.