[George McKay writes] I am delighted to announce the publication of Francesco Martinelli’s long-awaited EU Creative Europe-funded book, The History of European Jazz. It’s an impressively massive collection, in terms of scope and content, and has 40 chapters, one of which, on European jazz festivals, I wrote. My chapter is an output of the CHIME European jazz festivals project. The new book was launched at the 2018 European Jazz Conference in Lisbon a couple weeks ago, where, by the way, several CHIME team members were involved in the Jazz Researchers network meeting. Here is an extract from the opening of my chapter.

[George McKay writes] I am delighted to announce the publication of Francesco Martinelli’s long-awaited EU Creative Europe-funded book, The History of European Jazz. It’s an impressively massive collection, in terms of scope and content, and has 40 chapters, one of which, on European jazz festivals, I wrote. My chapter is an output of the CHIME European jazz festivals project. The new book was launched at the 2018 European Jazz Conference in Lisbon a couple weeks ago, where, by the way, several CHIME team members were involved in the Jazz Researchers network meeting. Here is an extract from the opening of my chapter.

… There is something quite remarkable across Europe about the contribution of promoters, producers, musicians and jazz enthusiasts to the development of jazz festival culture, which may have been overlooked in the scholarship, and which we can identify via a brief consideration of the pivotal US jazz festival, at Newport, Rhode Island. The inaugural Newport Jazz Festival, held in July 1954, was actually advertised as the ‘first annual American jazz festival’—and in that sense of ‘first … American’ festival rests an acknowledgement that the term jazz festival, and the very idea of an event such as a festival of jazz music, had already been invented elsewhere.

This was made clear to the restless crowd in the opening speeches at Newport that first night (the start of the live music was already running one hour late. Organisers and musicians alike were learning how to do a festival). The master of ceremonies was big band leader Stan Kenton (Duke Ellington wasn’t available), who was reading, and sometimes diverting, from a script written by Downbeat contributor Nat Hentoff. Kenton talked about the history and evolution of jazz in the US, and then turned to the subject of the new kind of event everyone had come to Newport to be at, saying:

This country has taken jazz for granted. Europe has recently held several jazz festivals, for abroad they recognise jazz as a distinct form of music. But only recently has this country accepted it as such. The Newport Festival is the first [jazz festival] to be held in this country and tonight makes history.

Impressively, Newport has gone on in the decades since to make a good deal more musical history. Yet prior history had already been made, as Kenton and Hentoff had informed their new festival audience, and it happened across the Atlantic: ‘Europe has recently held several jazz festivals’. So: can we say that the jazz festival was born in Europe? The jazz festival, which is today a near ubiquitous form of seasonal musical gathering and celebration, with common practices and features, networks, infrastructures, people and opportunities, took off in and echoed around Europe, and its burgeoning popularity was recognised and then swiftly imitated in the US.*

Among any other claims of jazz innovation Europe may feel it can make, this one may be worth sticking with. This is not an argument made for the purpose of cultural chauvinism—rather it is one presented to encourage us to think further about the complexities of innovation, transmission and circulation of live jazz music in the transatlantic frame.

That the early jazz festival was innovated and developed in Europe is striking—from the late 1940s on, that is, the very early postwar years in a devastated continent, the organisation and advertising of the new cultural event of the festival of jazz music began to take place. At the jazz band festival ball there was felt to be a good new buzz, and there was a collective spirit, and the idea spread quickly through the 1950s, and would go on to influence also the innovative rock and pop festivals and mass musical gatherings of the 1960s and 1970s counterculture.

That the early jazz festival was innovated and developed in Europe is striking—from the late 1940s on, that is, the very early postwar years in a devastated continent, the organisation and advertising of the new cultural event of the festival of jazz music began to take place. At the jazz band festival ball there was felt to be a good new buzz, and there was a collective spirit, and the idea spread quickly through the 1950s, and would go on to influence also the innovative rock and pop festivals and mass musical gatherings of the 1960s and 1970s counterculture.

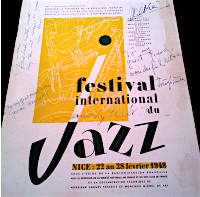

In the space of only half-a-dozen years the jazz festival spread, from, notably, Nice (1948) to Paris (1948 and 1949) and on to the Belgian coast at Ostend and Knokke (also 1948), to London (1949) to Newport by 1954. Following that, the journey behind the Iron Curtain took only a couple of further years (Sopot, Poland in 1956). Of these earliest festivals, we can reasonably say that Nice and Newport are the most notable, because of their extraordinary longevity. Nice and Newport have been with us most years, on and off, here and there, for many decades….

* Almost all originary claims are flawed, it is in the nature of the project. There is a plaque in a square in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania proclaiming it the site of ‘America’s First Jazz Festival’: ‘On February 23 1951 history was made…. Eight jazz bands got together for “The Cavalcade of Dixieland Jazz” which became the country’s first Jazz Festival’. Or perhaps this one: Randall’s Island Carnival of Swing, back in 1938. As reported in the New York Timeson May 30, ‘For a full five hours and 45 minutes, 23,400 assorted jitterbugs and alligators—more conservatively known as swing music enthusiasts—cavorted yesterday … to the musical gymnastics of 25 swing bands’. Or perhaps we should consider the Tournois de Jazz, live music competitions between dance bands with excited crowds, held in Belgium and the Netherlands in the 1930s, as versions of proto-jazz festivals. By the 1939 event the Tournoi was ‘a full-blown spectacle’, and included band contests, cutting and jam sessions, a dance-off, and even a Miss Swing competition.