Olle Stenbäck

What constitutes a music festival? The answer to the question would likely generate a number of answers, for example a limited geographical space, a question that soon turned out to be focal while conducting fieldwork on the 2016 installment of the GMLSTN JAZZ festival.

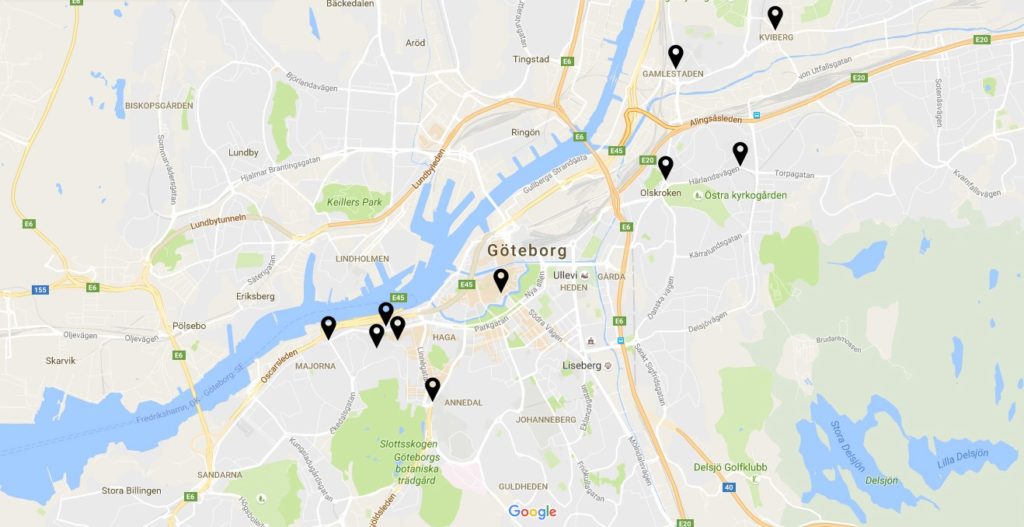

The 2016 installment of the festival took place on no less than 17 stages. The festival was dispersed all over the town of Gothenburg; spanning from pubs and churches in the suburbs, to established, renowned venues in the core cultural center. During the festival week in April 2016, we tried to map the festival as a whole in order to depict how it was distributed in the urban space and, equally important, how it appropriated it.

By interviewing members of the audience and analyzing answers from the online query we (Olle Stenbäck, Niklas Sörum and Helene Brembeck) made accessible during the festival week, we soon found that the lack of a limited, geographical space, raised questions among the festival goers. Some said that the festival, due to the dispersion, lacked a sense of community; a festival atmospheric.

Focus soon turned towards the theoretical term festivalisation, which is often used as a tool for critique. Researcher Nikolay Zherdev observes that urban planners attempt to “galvanize local cultural life” and “build a continuity of ‘happening’” to attract creative individuals (Zherdev 2014:5). Festivalisation have become a key concept for urban cultural production, whether it’s within the sports sector or city development; a part of the creative economy. Festivalisation marks a translation of sorts; transforming an ordinary event into something else, to differentiate. The term can also be used as an empirical, investigative tool to map the audience’s understandings of what a musical festival is and what it can be, which is how we operationalized it during the festival week.

“There is no generally accepted typology of festivals (Getz 2010:2, Mackley & Crump 2012:16f). From a North European perspective, there are several easily distinguishable types of musical events that are labelled festivals. One, especially common in the field of rock and pop, presents many acts on a few large stages over a rather short period of time (often a weekend) and in a limited, often fenced, space” (Ronström 2016).

Though there might not be a generally accepted typology of festivals, there’s obviously some understandings more dominant than others; the limited, often fenced space, being a distinct example of such.

While conducting fieldwork we were especially interested in finding out how – and/or if – the GMLSTN JAZZ festival committee worked to communicate the festival as part of the temporally translation of the Gothenburg jazz club scene into a more coherent festival space.

However, one of the focal ideas behind the GMLSTN JAZZ initiative is to function as a promotor, a unifying network, for the local jazz scene. Emphasis is put on tying scenes and venues together, where jazz – as a musical (yet broad) genre – is the unifying factor. The scenes/venues are not necessarily transformed into something else, but remains the same. They’re made part of the festival mainly by being represented in the festival program.

Apart from posters and festival programs, there wasn’t much that glued the 2016 installment of the festival together. In terms of communicating unity, there could have been more obvious visual-symbolic cues, moderating the festival goer’s experience, thus generating a uniform festival atmosphere.

GMLSTN JAZZ is still looking for its form. The festival is a young player on the musical festival field, which means there’s more – for them and us – to explore. In terms of branding mechanisms, the festival currently act mainly as an occasionally prominent, other times subtle, jazz promotor.