Author: Walter van de Leur

The Festival T-shirt

Judging from the crowds lining up at the stands that sell festival merchandise, the festival T-shirt is a much sought-after item. At the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival some of the T-shirt sold out quickly, at 35 USD a piece. The T-shirts at the Curacao North Sea Jazz Festival (CNSJF) carried a similar price tag, which, to the island’s economic standards made them even more pricey. Then again, with a ticket price of USD 180 per night, the festival is the most expensive I’ve witnessed so far. Those who have dished out that much money surely want bring to home a tangible souvenir, and the price is not going to stop them.

The fate of many festival tees must be pretty sad. I, for one, have a decent stack of them at home, but I basically wear them around the house when doing chores. After all, the quality is usually rather poor, they tend to fade after a couple of rounds in the washer and many loose shape quickly. Still, buying a shirt is clearly part of the festival fun, and all those newly printed shirts, caps, scarves and tote bags at the vendor’s area certainly look alluring. Many head for that section straight away.

At the Summer Jazz Bike Tour (ZJFT) I photographed people who wore ZJFT-shirts from earlier editions. The festival has no fixed logo so the design changes every year. Most images play with musical instruments and bicycle parts, bringing out the unique and playful aspects of the event (past posters here). The design for 2011 had a sax with handle bars, 2008 and 2015 had a pump-like device that ended in a trumpet (‘a pumpet,’ as team member Nick Gebhardt called it), and the 2013 design merged a double bass with a unicycle (that sounds smarter in English than in Dutch). Not only are these shirts collectibles, they are also the perfect gear for biking from concert to concert, especially if the weather is as good as it was this year. By contrast, the CNSJF makes for a classy night out, and the festivalgoers wore much more festive dress than a printed festival shirt.

Everybody I asked at the ZJFT gladly posed for me, and those modelling their tee often announced they had a shelve full of them, typically of all the editions they had visited. With a T-shirt one supports the event financially and connects with the other attendants. But there is more. By wearing a festival shirt, the ZJFT-ers celebrate the festival’s heritage and traditions, which they have helped to shape. Indeed, the ZJFT has a high number of returning visitors, who truly perform the festival together with the organizers. After all, the event is as much about its tangible locations and concerts as it is about the intangible activity of connecting those locations by cycling through the landscape. That active role is understood by the participants, and the festival shirt helps to express it all.

Curaçao Blog no. 1: Sun, Sea and Sand – and All That Jazz

(by Beth Aggett and Walter van de Leur)

The first day of September saw Amsterdam-based CHIME-members Walter van de Leur and Beth Aggett travelling to the Caribbean island of Curaçao to attend the ‘tropical edition’ of Rotterdam’s North Sea Jazz Festival. Curacao is a small island of around 160,000 people, lying just off the coast of Venezuela – indeed a good 8000km away from Europe and its jazz festival scene. It is however a former Dutch colony, with a rather turbulent past: Curacao was ‘discovered’ by the Spanish in 1499, conquered by the Dutch in 1634 and even seized briefly by the British in 1812 – all the while serving as an important ‘depot’ during the transatlantic slave trade (1640s – 1860s). Although it was primarily a trading post, there were around 100 small plantations established on the island during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, on which slaves lived and worked. Curacao’s central Caribbean location and free port meant it was also a stopping point for traders and travellers from all over, and it has a long history of in and out migration from the surrounding region and much further afield. The island is therefore connected to the European, African and American continents in myriad ways, resulting in a highly complex socio-cultural landscape. The locals’ mother tongue of Papiamentu, for example, displays components of Spanish, French, Dutch, English, and West African languages, and most Curacaoans are multilingual. In contrast, much of the architecture is distinctly Dutch, and there remain many tangible links to the colonial period. We noticed the Netherland’s coat of arms on government buildings, for example, and plaques commemorating visits of the Dutch royals displayed in town. Indeed it was only a few years ago that Curacao celebrated gaining independence; although the process of decolonization of Dutch Caribbean territory began in 1954, it wasn’t until 2010 that Curacao achieved full recognition as an autonomous country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Also in 2010: the very first Curaçao North Sea Jazz Festival (CNSJF). The country’s own charity organisation Fundashon Bon Intenshon produced this ‘sister’ event in collaboration with Mojo Concerts (owners of North Sea Jazz, who are themselves owned by the American company Live Nation). In bringing a ‘world-renowned festival brand’ to Curacao, the organisers hoped to attract a new demographic of visitors to the island – an international, wealthy, and sophisticated ‘jazz crowd’ – that would boost the country’s stagnant tourism industry. Like much of the Caribbean, Curacao’s economy is heavily dependent on tourists; its ‘sun, sea, and sand’ are the most important draw. The island’s capital of Willemstad, furthermore, has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its unique colonial architecture – another crucial selling point. Indeed, the festival’s CNSJF website describes it as an ‘untouched paradise’ with an ‘authentic’ and ‘historic’ centre and ‘vibrant’ culture.

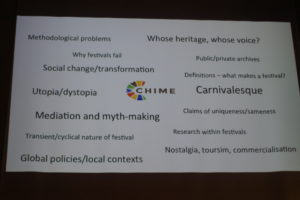

During the first lustrum of Curacao’s national independence, then, this small Afro-Curacaoan/Dutch/Caribbean/Central American island has been host to one of the largest and most significant events in the European jazz festival circuit/scene. CNSJF therefore is ideally situated to study a number of CHIME-related questions, such as the relationship between the festival and (constructions of) local cultural heritage. How are the heritages of both the festival location and the history of jazz music dealt with in the production of the festival? Does the music invite engagement with the heritage location, does it ignore it, or does it reconfigure the visitor’s relationship to place? In what ways can the presence of CNSJF act as a lens to interrogate concepts of cultural identity? Furthermore, how does the festival help us to think about the meanings and usages of jazz today? What are the possible synergies and frictions?

Interestingly, CNSJF is preceded by a low-key free festival called Punda Jazz that is organised by the bars and restaurants in the oldest district in Willemstad. With its strictly local acts, Punda Jazz provided an interesting counterpoint to its star-laden 180-dollars-per-day bigger sister across the bay. In our next blog post we will talk about our experiences at both events.

New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival: Performing the “authentic inauthentic”

I’ve just returned from a field trip to the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. True, New Orleans is not in Europe, but other than that the event ticks all the boxes of our CHIME acronym: Cultural Heritage, Improvised Music, and Festivals. Spread out over two extended weekends, Jazz Fest, as the event is commonly referred to, is fully focused on celebrating New Orleans’ and Louisiana’s cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible. Of course, the most obvious local music heritages are jazz and NOLA brass band culture, and despite the usual complaints that the acts on the main stages are not jazz but something else (Pearl Jam, Steely Dan, Red Hot Chili Peppers), there are many concerts on the smaller stages that are dedicated to musics that live up to the festival’s epithet, including jazz, brass band, zydeco, cajun, blues and gospel.

The main stages trumpet the names of the main sponsors (Acura Stage), yet other stages carry more descriptive names (Blues Tent, Gospel Tent), while yet others emphasize the connection with local traditions: Jazz and Heritage Stage, Congo Square Stage, Lagniappe Stage (the local term “lagniappe” refers to a gift or an extra), and Sheraton New Orleans Fais Do-Do Stage (a “fais do-do” is a Cajun dance party). The festival also exhibits folk crafts, arts and traditions in its Louisiana Folklife and Native American Villages. It celebrates local cuisines, too, for instance at the Grandstand, which “gives Festgoers a chance to take an intimate look at the vibrant culture, cuisine and art of Louisiana.” In addition, the festival has become a tradition itself, and many Festgoers have become regulars, who have developed their own traditions and rituals on the festival grounds.

Helen Regis and Shana Walton discuss in “Producing the folk at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival” the many tensions that center around questions of ownership, agency, race and authenticity. In Roll with it: Brass Bands in the Streets of New Orleans Matt Sakakeeny points up similar tensions, specific to the brass bands that perform at Jazz Fest.

Of special interest to me was the second-lining that takes place at Jazz Fest. Second-line culture in New Orleans centers around the many active brass bands in the city and the so-called Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs (SA & PCs), societies founded as black self help organizations. SA & PCs parade in their annual processions and at funerals. In a parade, the first line consists of the club members and the brass band. The bystanders who join in after the first-liners form the second line. Regis (2001, 13) points out that the term second line is ambiguous, as it refers to “multiple dimensions of the same phenomenological reality. It refers to the dance steps, which are performed by club members and their followers during parades. … [but] the term second line often is used to refer to the overall parade, including club, band and followers.”

SA & PCs parade at the festival grounds as part of the programming, but the local brass bands can mostly be heard at the Jazz & Heritage Stage and the Economy Hall Tent. Here too, second-line culture is put on display, but with the brass band on stage rather than leading the parade. As soon as the band hits an up-tempo song, the regulars at the Fest spring to their feet, open their umbrella’s–often self adorned–and start parading the tent, moving to the music. There is little here that resembles an authentic second-line parade in one of the city’s communities, yet it is as close as many of the Festgoers will ever get to this vibrant culture. Interestingly, these tent parades have become a festival tradition in themselves, and it is clear that to the participants the practice is an authentic expression. The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival celebrates local traditions, but has become a locus of newly created and invented traditions itself.

Festgoers second-line in the Economy Hall Tent to the music of the Paulin Brothers Brass Band

Bibliography

Hobsbawm, Eric and Terence Ranger, eds. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press.

Jones, David M., (director). 1995. New Orleans Jazz Funerals from the Inside. Documentary film. DMJ Productions, DMJ1018.

Regis, Helen A. 1999. “Second Lines, Minstrelsy, and the Contested Landscapes of New Orleans Afro-Creole Festivals.” Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Nov.): 472–504.

Regis, Helen A. 2001. “Blackness and the Politics of Memory in the New Orleans Second Line.” American Ethnologist, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Nov.): 752–777.

Sakakeeny, Matt. 2010. “‘Under the Bridge’: An Orientation to Soundscapes in New Orleans.” Ethnomusicology Vol. 54, No. 1: 1-27.

Sakakeeny, Matt. 2011. “Jazz Funerals and Second Line Parades.” KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. David Johnson, ed. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. 3 February.

Sakakeeny, Matt. 2011. “New Orleans Music as a Circulatory System.” Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Spring): 291–325.

Sakakeeny, Matt. 2013. Roll with It: Brass Bands in the Streets of New Orleans. Durham: Duke UP.

About the CHIME logo

The CHIME logo, designed by Marijn van Beek in collaboration with PI Walter van de Leur, captures some of the main ideas that come together in the project. The main form is inspired by the quote that opened our proposal:

The CHIME logo, designed by Marijn van Beek in collaboration with PI Walter van de Leur, captures some of the main ideas that come together in the project. The main form is inspired by the quote that opened our proposal:

“What an amazing experience, the clash of seeing Miles Davis in the Roman amphitheatre during the Nice Jazz Festival. The ancient stones and arches are resounded, the music somehow more resonant, old and modern at the same time. I’ll never forget that…”

The amphitheatre – its individual segments suggestive of castle towers — at the same time alludes to an LP record, while its colour scheme calls up the 1950s jazz cover art for Blue Note, Prestige and Atlantic.

The font of the lettering is called Montserrat, which is the name of a number of heritage sites across the world, from Catalonia to Buenos Aires. And yes, there is a Montserrat jazz festival (at the Montserrat College of Art, USA). And no, there are no bell chimes to be found in our logo.