A position paper (no. 1) presented to the CHIME project team meeting, Amsterdam Conservatory, February 4 2016

A position paper (no. 1) presented to the CHIME project team meeting, Amsterdam Conservatory, February 4 2016

Here are the opening sentences of the EU Heritage+ joint call grant application that the project team wrote in 2014, and which formed the basis of CHIME’s successful submission.

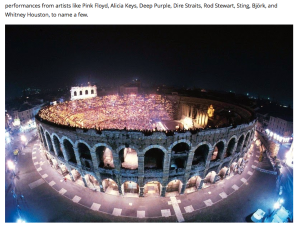

‘What an amazing experience, the clash of seeing Miles Davis in the Roman amphitheatre during the Nice Jazz Festival. The ancient stones and arches are re-sounded, the music somehow more resonant, old and modern at the same time. I’ll never forget that.’ This first-hand experience of a European festival-goer provided the initial inspiration for CHIME.

I (George McKay) want to interrogate the cultural space we have chosen a little further, which I hope will throw further light on my question, why look at jazz (and not, say, rock or folk) festivals?

There was a nice line tweeted on the CHIME Twitter feed recently, a quotation from Chris Goddard’s book Jazz Away From Home that sought to describe the experience of jazz in southern Europe, as a music ‘cut[ting] through the warm, humid Mediterranean night like a chainsaw through cheese’ (1979). Is jazz more cheese wire than chainsaw, do you think, though? If we want chainsaw music we need really to go to something more industrial—or agricultural—starting with the excessive, aggressive culture of rock music. Rock does after all sometimes feature a chainsaw: see southern US rock band Jackyl, who still finish each live set with their signature song ‘The lumberjack’ (the video is great and indeed a little Pythonesque, do have a watch) in which the lead singer does a chainsaw solo (though not through cheese). (Here is a pressing question for the New Jazz Studies: has a jazz band featured a chainsaw solo, ever?)

So, for questions of the clash or disjunction between heritage, festival site and popular music, the jarring re-sounding when both our ears double-take in stereo, rock music would be very good to think about. Though its history as a popular music has been shorter than folk or jazz (50-60 years as opposed to 100-120, very approximately)—does that mean its heritage is reduced?—rock music can supply a very powerful shock of the new, not least through its characteristic of being superloud, via a practice of extreme volume and a competitive rather than functional culture of amplification. (Even to the extent of rock deafening its bands and fans: McKay 2013, chapter 4.) And its use of chainsaws.

In order to pursue the comparison with Miles in the amphitheatre in Nice, consider an archetypal rock festival-style concert / documentary film, Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii (concert 1971, film 1972). (See film extract at end of blog below.)

- Filmed with the band playing live, over 4 days in October

- Used their full and extensive tour amplification

- Performances were filmed in front of no audience, an empty auditorium (rationale: in part a reaction against festival films like Woodstock, which had contained so many shots of festival-goers, the crowd)

- It’s a slow, spacey music the band plays, with some slow and lengthy camera focuses in/out and pans (2-3 minutes)

- Located in the ancient Roman amphitheatre and with a backdrop of Vesuvius

- Some key resonances: volcano/volume; block architecture of amphitheatre/PA/amp stacks

- Grandeur of the location fits with the grandeur (or pretentiousness) of Pink Floyd’s musical vision and its filming. (To return to the comedic end of rock, we could think here instead of Spinal Tap and their Stonehenge stage.)

Or consider Glastonbury Festival, originating at much the same time as the Pink Floyd concert (legendary Glastonbury Fayre was held in 1971, also filmed). Near Glastonbury, in the deep green English countryside, there is the invention of tradition and what I’m calling the instant ancient: mist and myth, a stage in the shape of the Great Pyramid of Giza, set on a ley line, with a crystal on top, a Neolithic stone circle—built around 1990.

This is the very place the boy Jesus was brought to by Joseph of Arimathea (so they say), the very place of the Isle of Avalon where Arthur, ‘the once and future king’, is buried (so they say), Glastonbury—where pagan and Xtian meet, and ‘the veil is thin’ (as 1930s occultist writer and ethical vegetarian Dion Fortune wonderfully put it: quoted in McKay 2000, 67).

Not only is Glastonbury possessed of a genius loci, but it has such a powerful genius loci that that spirit is magnified rather than diminished when festival invades each summer solstice. Rather than erase or complicate, the massified infrastructure and event of festival seems to amplify that most intangible of experientialities: the magic (or ‘magick’: Young 2010, ch. 13). In Electric Eden, Rob Young writes about ‘unearthing’ (visionary) music, uncovering folk-rock-landscape links and electric shocks.

Remember, one of our research questions is: how do music festivals (not jazz festivals explicitly) blur the boundaries between tangible [and] intangible … heritage? I have touched on the problem of the critical articulation and interrogation of ‘the often elusive or discarded cultural traces’ of writing about festivals elsewhere. For example, from 2015’s The Pop Festival:

there are some persistent difficulties with such critical terrain. Tracing the influence or impact of some cultural forms at the time under discussion is problematic, due to their elusive, emotive or transitory nature, and the festival as a carnivalesque combination of pop and protest is emblematic in this context…. Also, such cultural forms and practices have not always been treated well over the course of time—some have been discarded, or forgotten, or remembered without prestige. (McKay 2015, 16)

One of our project objectives is ‘[t]o interrogate the relationship between music and place’. Equally it might be useful to think about folk music for these questions of place, resonance, heritage, in the special heightened zone of the festival. Here the situatedness of folk, its shall we say fetish of place, its songs that are about place, and often about the past, in voice or accent and in narrative lyric story alike, may offer ways in. I mean, sometimes at the more purist/puritanical end of the second folk revival in Britain in the 1950s the law was that you could only sing songs in the folk clubs from the place you came from. Folk singer and activist Ewan MacColl expressed the policy line more ideologically: ‘we should be pursuing some kind of national identity, not just becoming an arm of American cultural imperialism’ (quoted in McKay 2005b, 55). (Was jazz better suited to that?)

Compare these urgent questions of place and music in folk with the global or hemispheric or ‘outernational’ form of jazz. The Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek articulates the binary power of jazz as world music, as global culture, and begins to move towards a critique of it.

‘World music’ to me has at least two meanings. First of all the regular meaning—a music composed of ethnic elements from various parts of the world. But on the other hand, American pop music is the real world music. It’s everywhere in the world and everybody listens to it whether they like it or not. (quoted in McKay 2005a, 11; emphasis added)

Does jazz have any of those homogenising and flattening features of world music, and not in a good way? If it does, how useful is it for thinking about place? And if jazz is a largely instrumental form, does that mean that lyrical reference to place as subject is weaker still?

But, lest this begin to sound like a statement of disavowal of the jazzy aims of CHIME, let’s see if this initial material can reflect usefully back on jazz, on the jazz festival. What opportunities does our focus specifically on jazz give us? What might we be losing, or making more difficult for ourselves? What do we gain?

The urban.

Possibly jazz does not generally require genius loci of its festivals—and indeed may view it as a nostalgising desire from a landscape tradition that doesn’t readily admit the urban, the modern. The jazz festival, then, as metropolitan cosmopolitanism, differs. As Anne Dvinge reminds and challenges us: ‘[a]ny city festival may achieve a temporary transformation of the urban.’ What interests us should be ‘the specific contribution of the musical practice that is jazz to making a particular kind of festival and transformation’ (Dvinge 2015, 185).

Ancient and modern.

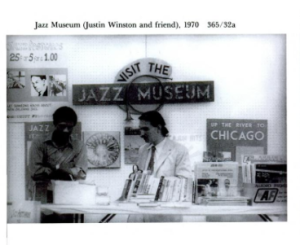

Although jazz likes a sheen of modernism, seeks regularly to rebirth the cool or claim futurity, in fact its selling point today may primarily be its heritage. This is seen in the names of some festivals—the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, most obviously, of course, established in 1970 (see right, with museum stand). For all its repeated rhetoric of cutting edge, it is arguably a music less of innovation and more of reflexivity today. Besides, all those cover versions, boringly referred to as ‘standards’, mean it has a repertoire which has always revisited itself. Can we say jazz performs the dialogue between old and new (even in its classic instrumentation: traditional analogue/acoustic orchestral instruments like grand piano and double bass, alongside the modern inventions of saxophone, kit drum, electric guitar or keyboard on the other)?

Playing in the moment.

Also, improvisation, the lauded liveness and nowness of jazz music (even if it’s recorded—and jazz recordings are complex objects: ‘powerful’, ‘seductive’, ‘menacing’ even: Whyton 2013, 3)—is a performative gesture that can lead us to compelling cultural questions of intangibility—of experience, of heritage. The free-floating signifier of music, all music—melting into the air—is doubled or multiplied in jazz via its improvisatory impulse. It becomes a case study in difficulty of capture, possibly even the degree zero of that project. Thus: a great intellectual challenge.

Intangibility.

For American saxophonist Dave Liebman, jazz (Coltrane anyway) is ‘something beyond words, beyond the music’ (quoted in Whyton 2013, 7); for South African pianist and bandleader Chris McGregor ‘music is in fact very, very precise: it says exactly what words are unable to do’ (quoted in McKay 2005a, 301). I wonder whether there is some thing (transcendent) in these claims that makes jazz about intangibility, inexpressibility. In Alan Rice’s view, ‘[j]azz culture … [has an] easy acquaintance with the dangers and pleasures of evanescence and remembrance’ alike (2010, 126). Here is another powerful one, from African-American novelist James Baldwin, on the culture, politics and origin of jazz:

This is exactly how the music called jazz began … to checkmate the European notion of the world.… [T]here is a very great deal in the world which Europe does not, or cannot, see: in the very same way that the European musical scale cannot transcribe—cannot write down, does not understand—the notes, or the price, of this music. (Baldwin 1979, 326)

Expressibility.

Of course the music is also historically firmly, in fact violently, located, in the forced and murderous mass migration of transatlantic slavery. As James Campbell put it, ‘[w]hat sets black American music apart from other folk musics is the circumstances of its creation, which is what gives it its sense of urgency’ (1995, 5). For Rice, ‘African American musicking is the key mode of transmission of a diasporic, routed culture’ (2010, 107).

Carnivalesque.

Also we can argue that jazz has a special place in the story of music as festival: think of calypso, reggae, carnival, and most of all jazz and blues—formed from the experience of global or hemispheric circulation (the triangulation of the Black Atlantic: see Gilroy 1993, Rice 2003), and even in the case of jazz birthing prior to the development of mass media that would give later, newer musics rapid international profile. Carnival is at the core of jazz: parade bands, Mardi Gras, Congo Square, second lining…. This is my central thesis for the study of the jazz festival, as opposed to rock, or folk, say. There is no jazz without festival, there is no festival without jazz. (Discuss.)

Jazz utopia.

Jazz utopia.

(Since we are organising an international conference on the subject with over 100 speakers from around 25 countries as part of the Rhythm Changes series.) This returns us to Dvinge’s point from earlier, about the specificity of jazz, of the ‘sonic space’ of the urban jazz festival, in all of this.

During the jazz festival,… [t]his sonic process is not (only) an echo of times past but a resonance on what is. At the jazz festival things come together and we fall into step. These memories function not as reactionary, backward-looking stoppages in the community. Rather, they are what places are made of—a series of what-used-to-bes that offer the material for what can be. (Dvinge 2015, 195)

How much further, and in what directions, can we in CHIME push (our understanding of) this (kind of utopian) vision?

- Baldwin, James. 1979. ‘Of the sorrow song: the cross of redemption.’ In Campbell 1995, 324-31.

- Campbell, James., ed 1995. The Picador Book of Blues and Jazz. London: Picador.

- Dvinge, Ann. 2015. ‘Musicking in Motor City: reconfiguring urban space at the Detroit Jazz Festival.’ In McKay 2015, 183-97.

- Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso.

- Goddard, Chris. 1979. Jazz Away From Home. London: Paddington Press.

- Jackyl. 1992. ‘The lumberjack.’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A52p9jc-gOo. Accessed 2-Feb-2016. Music video.

- McKay, George. 2005a. Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain. Durham Duke University Press.

- ———. 2005b. ‘ The social and countercultural 1960s in the USA, transatlantically.’ In Christoph Grunenberg and Jonathan Harris, eds. Summer of Love: Psychedelic Arts, Social Crisis and the Counterculture in the 1960s. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 35-62.

- ———. 2013. Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability. Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press.

- ———, ed. 2015. The Pop Festival: History, Music, Media, Culture. London: Bloomsbury.

- Rice, Alan. 2003. Radical Narratives of the Black Atlantic. London: Continuum.

- ———. 2010. Creating Memorials, Building Identities: The Politics of Memory in the Black Atlantic. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Whyton, Tony. 2013. Beyond A Love Supreme: John Coltrane and the Legacy of an Album. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Young, Rob. 2010. Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music. London: Faber.