A position paper (no. 2) presented to the CHIME project team meeting, Amsterdam Conservatory, February 4 2016

A position paper (no. 2) presented to the CHIME project team meeting, Amsterdam Conservatory, February 4 2016

In WP3, CHIME explores ways in which music and music festivals can provide new models for thinking about cultural heritage through an exploration of festival landscapes. It does so, among other things, by looking at three case studies, all of which are selected specifically for their engagement with different types of cultural heritage: North Sea Jazz Festival Curaçao, the SummerJazzCycleTour, and Jazz on the Waves. In this position statement I [Loes Rusch] propose a further exploration of music and music festivals as 1) practices of cultural heritage and 2) as a promotional tool for the protection and preservation of natural cultural heritage sites.

While the North Sea Jazz Festival Curaçao raises questions of the Netherlands’ colonial past and the ways in which different identities are negotiated through festivals, the SummerJazzCycleTour and Jazz on the Waves are particularly interesting because of its different approaches towards the re-use of typical Dutch landscapes and historical buildings.

The SummerJazzCycleTour, which  celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, takes place in the province of Groningen in the north-eastern part of the Netherlands and makes its audiences cycle through the Reitdiep, an agricultural area with canals dug as early as the first half of the thirteenth century. Jazz on the Waves takes places on the island of Texel in the Wadden Sea, an intertidal zone in the south-eastern part of the North Sea, which is one of the world’s seas whose coastline has been most modified by humans, via a system of dikes and causeways on the mainland and low-lying coastal islands. In 2009, this area became part of UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, takes place in the province of Groningen in the north-eastern part of the Netherlands and makes its audiences cycle through the Reitdiep, an agricultural area with canals dug as early as the first half of the thirteenth century. Jazz on the Waves takes places on the island of Texel in the Wadden Sea, an intertidal zone in the south-eastern part of the North Sea, which is one of the world’s seas whose coastline has been most modified by humans, via a system of dikes and causeways on the mainland and low-lying coastal islands. In 2009, this area became part of UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Jazz and cultural heritage

The relationship between music or music festivals and cultural heritage is extensively studied, mostly in the area of popular music. The focus of these studies is mostly on the practice of music as cultural heritage, or as defined in a 2014 study by Amanda Brandellero and Susanne Janssen as “the preservation, exhibition, education and remembrance” of music, in many cases as supported and promoted by national and local public heritage institutions, often in connection with spatial planning and cultural tourism (Brandellero and Janssen 2014, 18).

While this definition takes music as its prime object, jazz and improvised music in the case of the SummerJazzCycleTour or Jazz on the Waves can—and should—also be understood as part of the promotion of cultural and natural heritage sites and thus as a promotional tool, subordinate to the marketing of Dutch natural heritage sites and historical buildings. This function becomes clear by looking, for example, at the festivals’ sponsors. One of the main sponsors of the Summer Jazz Cycle Tour is the Stichting Oude Groninger Kerken (Groningen Old Churches Foundation), a foundation that is currently responsible for the protection and preservation of sixty-three historic churches and two synagogues in the province. It has been the festival’s partner from the start. Also tellingly, the slogan of the festival, as shown on the documentary that was made as part of the festival’s 20th anniversary is entitled “SummerJazzCycleTour: Music for cycling landscapes”.

Similarly, Jazz on the Waves is supported and promoted by, among others, the tourist office and a number of campsites. Thus, while music and music festivals can be understood and studied as cultural heritage, I propose in our case a further exploration of jazz as part of natural heritage promotion and thus as a marketable commodity that can be deployed as part of place promotion activities. Moreover, I would like to argue, that studying the interconnectedness between these two types of cultural heritage could provide us with new insights in cultural meaning-making.

Underlying my proposal is the idea that all types of cultural heritage is first and foremost a discursive practice that is grounded both in time and in place, and which therefore necessarily translates into a material culture that can be studied and investigated. This moves beyond the distinction between tangible and intangible heritage as proposed by UNESCO in 2003, the year in which the organisation included the performing arts and festive events in its list of intangible heritage, which is defined on their website as “traditional, contemporary and living at the same time,” “inclusive,” “representative” and “community-based”. However, rather than focusing on the intangibility of music and festive events, I propose that a focus on the materiality of festivals and music by studying the connectedness to a geographic place, has the potential to gain new insights into the ways in which music and festivals contribute to the construction of a sense of place, and to the significance that landscapes, sites and buildings hold for its users.

Festival Nieuwe Muziek

The Netherlands is especially interesting for exploring the interconnectedness between jazz as cultural heritage and landscape promotion because it has a relatively long and fascinating tradition of outdoor jazz festivals. One of its most fascinating examples is New Music Festival, which was organized between 1974 and 2004 in the coastal province of Zeeland, in the south-western part of the Netherlands. Initiator Ad van ‘t Veer wittingly used the changing political climate and the policy of cultuurspreiding—the geographical distribution of art and cultural institutions from the cities in the west to all areas of the Netherlands—to create a festival that challenged conventional boundaries between low/high art, audience/artists, performance/surroundings, and between different forms of art.

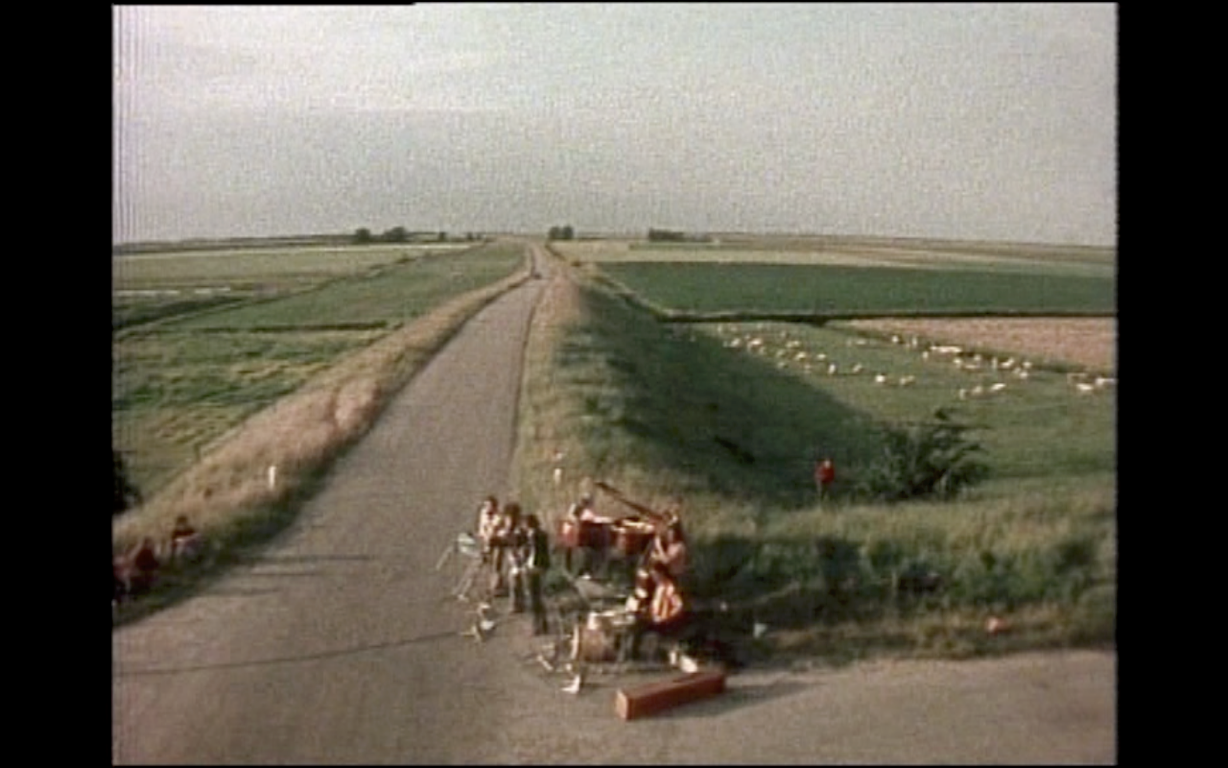

Screenshot Zeeland Suite documentary, 1977

Screenshot Zeeland Suite documentary, 1977

In an earlier exploration of the 1977 performance of the Zeeland Suite, a composition commissioned by the festival, I discussed ways in which the New Music Festival, by conforming to the agenda’s of funding institutions—in this case music as a promotional tool for the province of Zeeland—state-funding stimulated a further exploration of national narratives in jazz (Rusch 2015).

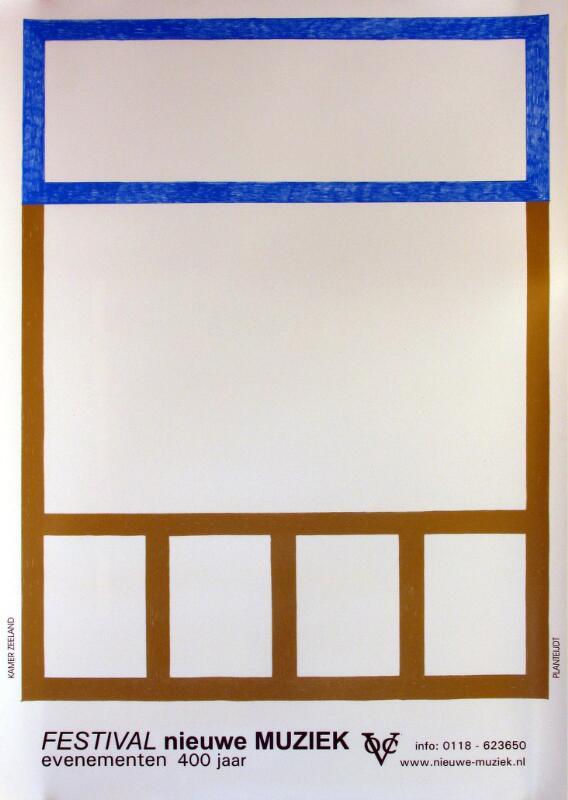

Throughout the years the festival and the performances became increasingly interwoven with local heritage sites and ideas of local and national identity. For example, the festival programmed a mix of international contemporary composers such as Xenakis and typical Dutch improvising musicians such as Willem Breuker and Misha Mengelberg; the festival also collaborated with local artists to design the posters; further it integrated the landscape into musical performances; and the festival in different ways connected to national and local narratives. In 2002, for example, the events of the festival were all part of the 400-year anniversary of the Dutch East India Company VOC—the VOC logo can be seen on that year’s poster.

Altogether, the festival shows how musicians, producers and media gratefully used the very explicit link with Zeeland as either creative material, funding argument, or representational tool, in the process implicitly or explicitly contributing to the recontextualizing (or what some may consider the appropriation) of jazz as a Dutch and thus non-American art form. Moreover, it shows how public funding institutions not only provided the necessary financial means but also played an active, transformative role in the establishment of improvised music. This way, the Festival New Music played a crucial role in the construction of a sense of place and of local narratives, connecting past experiences with present day locality (Rusch 2015).

Ultimately then, the historical case of the Festival New Music demonstrates how the study of musical performance and festive events in relation to space—albeit financial, performative, or geographical—can contribute to the understanding of how narratives of national culture are told. In the next few months I would like to explore the possibilities for implementing these ideas and findings on our case studies.