Heritage is a contested subject that is bound up with concepts of memory, belonging, cultural value and the politics of power, history and ownership. However, as Laurajane Smith stresses, heritage is not only about celebrating and appreciating the value of material things that have been passed on from one generation to the next but it is also a communicative act that encourages people to make meaning for the present day. Heritage enables us to celebrate and understand not only who we are but also what we want to be (Smith: 2006, 1-2).

If we accept that heritage is not necessarily a thing but a process it leads us to consider the possibility that all heritage – and that includes the notion of a heritage site – is intangible by definition. Smith continues,

While places, sites, objects and localities may exist as identifiable sites of heritage… these places are not inherently valuable, nor do they carry a freight of innate meaning. Stonehenge, for instance, is basically a collection of rocks in a field. What makes these things valuable and meaningful – what makes them ‘heritage’, or what makes the collection of rocks in a field ‘Stonehenge’ – are the present-day cultural processes and activities that are undertaken at and around them, and of which they become a part. It is these processes that identify them as physically symbolic of particular cultural and social events, and thus give them value and meaning.

(Smith: 2006, 3)

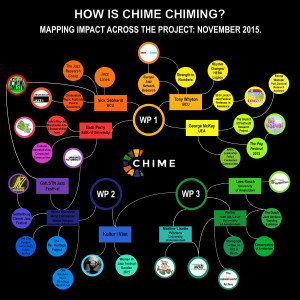

Using this idea as a starting point, CHIME’s interpretation of heritage sites leads us to places that have become symbolic of particular social and cultural events, where values and meanings have been ascribed and where identities are constructed, re-constructed, suppressed or negotiated.

Within this context, heritage sites can obviously include officially listed buildings and places of historical importance, conservation areas, and protected sites of natural beauty. I’m sure we have all visited buildings that are in possession of national trusts or heritage organisations as well as accredited UNESCO World Heritage Sites. But our definition of heritage sites is not be limited to state-funded or officially managed heritage institutions. We also look more broadly to places where acts of remembrance or commemoration offer meaning to specific groups, to locations where people negotiate a sense of belonging and/or (re)consider their place in the world. Or, indeed, to places which encourage us to reflect on our relationship to the environment or which provide us with a transformative vision of the future.

Festivals, Heritage, Utopia

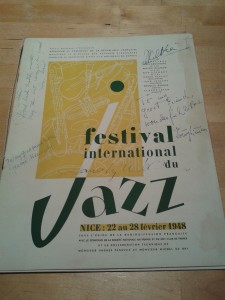

It is within these latter points that the relationship between jazz festivals, heritage sites and utopian thinking comes into focus. Utopia has been widely discussed as both an appealing and dangerous concept wrought with problems and idealised assumptions (De Geus, 1999). Moreover, within studies of festival cultures, there seems a natural synergy between festivals and utopian concepts, given the transformative potential of places, spaces and social practices within evanescent events or carnivalising  atmospheres. Indeed, within McKay’s recent edited collection The Pop Festival (Bloomsbury, 2015), concepts of utopia form a central theme within the book, and within his introduction, he outlines ways in which contributors explore concepts of utopia in contrasting ways; for example, as something celebrated, critiqued, glimpsed, denied, dreamt or nightmared. And yet, despite these contrasts, McKay stresses that,

atmospheres. Indeed, within McKay’s recent edited collection The Pop Festival (Bloomsbury, 2015), concepts of utopia form a central theme within the book, and within his introduction, he outlines ways in which contributors explore concepts of utopia in contrasting ways; for example, as something celebrated, critiqued, glimpsed, denied, dreamt or nightmared. And yet, despite these contrasts, McKay stresses that,

[Festival], at its most utopian, is a pragmatic and fantastic space in which to dream and to try another world into being.

(McKay: 2015, 5)

Rather than utopian thinking being founded on idealised principles, the concept can provide a critical framework from which to challenge established conventions, political practices and naturalised assumptions about the world. Within a jazz context, utopia can be useful when it provides a means of challenging presuppositions, encouraging a continual sense of reflexivity about the music’s ontology and its cultural relevance, and keeping the present in dialogue with the past.

‘The Heritage’

By adopting this approach, the study of heritage sites becomes a form of discursive practice and we should be mindful here of the power and all-pervasiveness of what Stuart Hall described as ‘The Heritage.’ (Hall, 1999) For Hall, the heritage becomes,

‘the material embodiment of the spirit of a nation’, it is a collective representation of tradition or of valuable places and objects that, ‘[t]o be validated, must take their place alongside what has been authorised as ‘valuable’ on already established grounds in relation to the unfolding of a ‘national story’ whose terms we already know.’

(Hall: 1999, 3-4)

These reified presentations of heritage can structure ideas not only about the past but can also play down, ignore or exclude issues of race, gender, class, and disability that would inevitably provide a challenge to official and uncomplicated interpretations of nations and associated cultural narratives. Despite a number of changes to understandings, formations and uses of heritage in recent years, ideas of nationhood can often remain naturalised and colonial histories treated as remote and unproblematic; there is no scope for complexity, contestation or a multitude of voices in the world of ‘The Heritage’.

Envisioning the future, reconciling the past

Building on this, the role of jazz and improvised music can be a crucial element in disrupting established ways of thinking about heritage and determining the significance of sites in question. When jazz enters particular spaces, it can provide a means of engaging with established discourses, reconfiguring histories, encouraging a renewed perspective on a particular location, or re-engaging with the past.

Building on this, the role of jazz and improvised music can be a crucial element in disrupting established ways of thinking about heritage and determining the significance of sites in question. When jazz enters particular spaces, it can provide a means of engaging with established discourses, reconfiguring histories, encouraging a renewed perspective on a particular location, or re-engaging with the past.

Through our research, we will aim to investigate a diversity of voices through festival sites. We want to convey the meaning places afford to different people, understand the stories that enliven specific objects, or explore how narratives that generate cultural mythologies feed into other narratives that offer meaning to contrasting groups. As a transnational study, CHIME will explore how global events link to local cultures and shape the lives of people in different ways. Through festivals we can consider how sameness and difference can play out in different geographical settings; the ‘heritage site’ in this context can offer a challenge to narrowly defined understandings of the world, of people and places.

When CHIME examines a heritage site, therefore, it does so with these processes in mind and, in developing a typology of festivals and heritage sites, it will be important to consider different ways in which the heritage question plays out for different communities in a range of European places.

References

De Geus, M., Ecological Utopias: Envisioning the Sustainable Society (Utrecht, International Books, 1999)

Hall, S. ‘Whose Heritage? Unsettling ‘The Heritage’, Reimagining the Post-Nation’ Third Text 13:49, pp.3-13

McKay, G. (ed.), The Pop Festival: Hiostory, Music, Media, Culture (London: Bloomsbury, 2015)

Smith, L., Uses of Heritage (New York: Routledge, 2006)